Washington Redskins Cheerleaders: All work, (almost) no pay

By Amanda Hess

TBD.com

Photos by Matthew Beck

Fans at FedExField for last November’s game between the Washington Redskins and the Minnesota Vikings were instructed to pay close attention: a Pro Bowl berth was about to be announced. Who would it be? A camera panned up and down the field as the audience sat wondering who would receive the honor.

The suspense ended when the camera zoomed in on the winner, as the announcer proclaimed, “Chelsea!”

Chelsea hadn’t run for 1,000 yards or recorded 20 sacks or returned four kickoffs for touchdowns. She’d been on the sidelines, kicking and dancing for the pleasure of the fans. She apparently did it quite well, or well enough that she was chosen to represent the Washington Redskins Cheerleaders in Honolulu.

Too bad that the Redskins fans will never know who she really is. No last name came over the PA system that day, just “Chelsea.” Imagine the league identifying its all-time leading rusher simply as “Emmitt.”

That the Redskins’ standout cheerleader should remain identity-less, though, squares with her status in the organization and the league. As the NFL labor wars move from the courtroom to press conference and back, all the talk centers on fairness: How to divvy up the NFL’s $9 billion pie?

At the table are the players, the former players, and the owners, all of whom are fighting to get even richer.

And the cheerleaders? Well, whatever all the men decide, they’ll be ready to lose out on plenty of money for the privilege of smiling about it all.

At a Sterling, Va., Gold’s Gym one March afternoon, a few dozen young women have assembled for “Project Cheerleader,” a three-hour seminar that lays the track to the sidelines of FedExField. Inside, cheer director Stephanie Jojokian leads a stable of current and former cheerleaders, makeup artists, hairstylists, and spray-tanners in airing their tips for making the squad. “Please don’t have a nervous breakdown,” says Jojokian, pregnant in a cream-colored sweater, faded jeans, and cuffed slouchy high-heeled boots. “Any suggestions we give you are to help you.” Attendees have paid $50 for the competitive advantage.

The average investment in an NFL cheerleader audition extends far beyond the know-how. “There’s a lot you can do to mentally prepare yourself to accomplish this goal,” one audition expert informs the women. “But you also need to have the look.”

And the look comes with a price tag. “I want you to understand, makeup is the quintessential factor in choosing who we choose for the team,” celebrity makeup artist and certified minister Kym Lee tells the women of Project Cheerleader. “Most of the girls who come to me . . . they make the team,” she says. “That’s the bottom line: How bad do you want it?” (Audition-day make-up touch-up by Lee or a member of her staff: $75).

Trainers from Gold’s Gym prepare the women for “a lifestyle change,” one that requires them to eat less and exercise more. “I know we’re here so we can all look freaking amazing for the Redskins and make the squad,” Tommy Houck, the gym’s director of personal training, tells the hopefuls. “It’s also about health.” (A standard Gold’s Gym membership: $36.99 per month).

Later, spray-tanners from Ninotch invite the women to cake on one of its 22 custom-blended organic skin tints, with extended spraying hours available pre-audition. Pale girls should schedule two appointments to “avoid the Snooki look” of “getting dark too fast.” No shade is safe: “I just want to say, black girls get sprayed too,” says cheer co-captain Kelly. (Ninotch’s advertised rate for a full body treatment: $45)

“When you’re looking down from the stands, you want to see that the cheerleaders have life,” one expert tells the crowd. “You want to see them animated. You want to see they have body in their hair.” At the seminar, Nicole White, a former Redskins cheerleader ambassador, delivers an impassioned testimony for the salon that cured her Afro. “Nothing wrong with the Afro,” White says, “but it wasn’t the best look for me.” Or for any cheerleader: “Every practice you have to wear your hair out,” Kelly tells the black women in attendance. “It has to be done. Shampoo, blow dry, flat iron, curl.” (A rep from Wheaton’s Ultimate U says that a full head of extensions runs $270).

Representatives from a Lasik eye surgery provider advise the women to let a surgeon “get you out of your contacts,” just “one last thing to worry about before your auditions.” (The going rate for LASIK eye surgery: $1,500-$2,200).

After the spiel, hopefuls page through a rack of sparkly spandex two-pieces from The Line Up. “Don’t cover your chest area too much,” Jojokian schools the women on their audition-day attire. “We’ll assume you are trying to hide something.” And “if we tell you to change your top, do it,” she adds. “The fact that we’re coming up to you and telling you this is a good sign.” (The Line Up’s tops range from $56 to $84; bottoms go for $38 to $76).

When they leave here, the women are instructed to “take as many prep classes as possible,” even “if you have danced your entire life.” (A full 10-class program from the Washington Redskins: $250). Women in need of extra help are told to enroll in a jazz class with Jojokian at Capitol Movement ($15 per session).

Aspiring cheerleaders looking for a leg up can always cinch an advanced degree. The Redskins website publishes a collection of photos illustrating the essential character of a Redskinette: She must be “talented” (a line of cheerleaders execute a high kick); “flirtatious” (a cheerleader stares with lust from the sidelines); “sexy” (a cheerleader bends over to reveal her cleavage); and “intelligent” (two cheerleaders bend over to reveal their cleavage). At Project Cheerleader, women sporting two-inch inseams emphasize their academic qualifications. Cheerleader Buffy is working on her doctorate in physical therapy. Talmesha is a Ph.D. student at Johns Hopkins University medical school. Amanda hopes to secure a master’s degree in broadcast journalism. Donna minored in women’s studies. “See?” Jojokian says of her highly educated squad members. “She’s smart, too!”

When does it end? “Take a picture of yourself,” Lee instructs the women. “Look at the picture, and then look at the girls on the website and see if you look similar to that.” Each woman in attendance looks is if she’s already completed the seminar’s tasks backwards in high heels: top and bottom lids lined, eyelashes curled and extended, hair relaxed and blown out, tummies tight, feet carefully fitted into nude platforms. But a professional cheerleading audition ($40 application fee) is a whole other ballgame. “Are you going to do it?” one potential cheerleader asks another about Kym Lee’s $75 audition-day makeup touch-up. “I feel like I should do everything they tell me to do,” she tells her.

If an aspiring cheerleader opts for each of these suggested modifications, she’ll be out a few thousand dollars before she even auditions for the squad. But so what? A salaryman looking for a job in corporate administration invests big dollars in suits, cufflinks, and ties. An aspiring professional athlete sinks bank into trainers and diet. But it’s only an investment if you stand to make a return.

Cheerleaders who make the cut are paid $75 per home game performance. With eight games and a couple of preseason bouts at FedExField on the schedule, full compensation for a season of on-field entertainment can amount to less than $1,000. Redskins cheerleaders also receive a pair of season tickets. Of course, they’ll have to find someone else to fill the seats—they’ll be working.

The Redskins say cheerleaders log “12 to 20 hours” of work for the team every week. That’s probably low. According to cheerleader testimonials at Project Cheerleader, women attend two to five mandatory practices each week, which sometimes start at 6 p.m. and extend to midnight. Cheerleaders must learn their choreography on their own time, studying DVDs of routines before key practices. Throughout the summer, the women practice as a squad. And that doesn’t include the hours of tanning, dieting, exercising, makeup applying, hair styling, and bra-pinning necessary to make the cheerleaders field-ready.

Once the season starts, game days can be 12-hour affairs. To make a 1 p.m. start time, 29-year-old Buffy wakes up at 5 a.m. She hits the shower, does her hair and makeup, and arrives at FedExField by 7:45. At each stadium arrival, “it’s important we present ourselves in the best light possible,” Buffy says. During the game, she’ll execute halftime and sideline routines. She’ll drop to the splits in the kickline. She’ll represent the team in events and promotions throughout the afternoon. And no matter what she’s doing, she’ll always look the part. “When a commercial comes on,” says fellow cheerleader Dawn, 28, “you’re cheering for that commercial.” The day’s duties won’t end until 6 p.m.

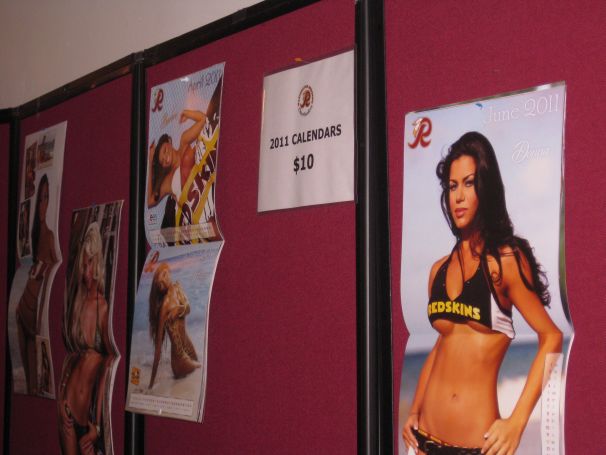

Each spring, cheerleaders set aside eight full days for the organization, too. That’s when they travel to an “exotic location,” where they’ll produce enough primo shots for 16 months of calendar. At last year’s Punta Cana shoot, the Redskinettes tinkered with provocative poses for days. Several cheerleaders appeared with only footballs, hands, or pink roses covering their breasts. Others just wore paint. In shoot videos published on the team website — which sidle up to ads from Verizon and Audi — the women romp in the surf and dish about what they look for in guys. The Redskins sell the resulting spread for $14.99 a pop.

The Redskins say the shoot “includes airfare, hotel and all meals,” but Jojokian warns Project Cheerleaders that squad members are required to secure their own passports and set away their own vacation time for the mandatory trip. The Redskins won’t comment on whether these women are actually compensated for eight straight days of highly revealing modeling work. “I’m sorry,” Redskins Senior Vice President Tony Wyllie told me via email when I asked for comment on the cheerleaders’ pay: “we can not help here.”

The Redskins won’t confirm what wages the cheerleaders bring home, but the women drum up plenty for the team. Each year, the Redskins make each cheerleader available for more than 20 official appearances, where they dance, sign autographs, and pose for photos at private parties and corporate events. Unlike Redskins players, the team’s cheerleaders can’t set their own appearance fees, and the team won’t disclose its price tag of a Redskinette at your doorstep. But across the league, NFL teams charge outside organizations an hourly rate that far outstrips the women’s game-day pay. The Baltimore Ravens, for example, charge appearance fees of $150 to $250 per cheerleader per hour. The Tennessee Titans charge up to $300 an hour. And the Oakland Raiders rent their cheerleaders at a $400 hourly rate. It’s not clear what portion of those appearance fees actually trickles down to the talent.

When NFL cheerleaders aren’t turning a profit for the teams, they’re pulling heartstrings on feel-good PR missions. The women of the Redskins volunteer their services by visiting veterans’ hospitals, hopping on antique fire trucks, and patronizing “green” hair salons, all to burnish the team’s public image. “Aside from the lipstick, eyelashes, and hairspray, this is a very reputable organization to be a part of,” says cheerleader co-captain Sabrina of the squad’s charity work.

Redskins cheerleaders also lend their talents to autographed squad photos ($20), authentic pom-poms handled during games ($50), and a full-service iPhone app available only to fans 12 and older ($1.99). The women occupy significant real estate on the team website, where their highly clickable photos lounge next to ad space for Kenny Chesney, Bank of America, and Toyota. In 2009, the Redskins enlisted the women into a listener contest for Redskins owner Dan Snyder’s sports station, WTEM-AM. The prize: Cheerleaders in bikinis wash your car. The event required the women to “put down your pom poms and grab a sponge!”; a radio promotion teased that the auto was just a stand-in for the fantasy of cheerleaders “soaping up and scrubbing you.”

And the Redskins aren’t the only ones making money off their backsides. Comcast SportsNet carries a “Beauties on the Beach” video series starring members of the squad. The NFL sells snapshots of the cheerleaders on its website for anywhere from $15 to $389.

This is where gridiron sexism hits with full force. Football players are paid for the use of their likeness thanks to a group licensing agreement with the NFL Players Association, but the cheerleaders have no such deal. “We do not pay them,” NFL spokesperson Brian McCarthy told me via e-mail. “The teams pay their cheerleaders. As part of their agreement with the team to become cheerleaders, they understand that they will not be paid additionally if their likeness is used in this manner. Our office doesn’t get involved.”

It’s possible to run a successful professional football team without the aid of cheerleaders; six NFL teams don’t employ the pom-pom shakers. But you might not be able to run a team as financially successful as the Redskins. Forbes this year valued the organization at $1.6 billion, making the Redskins the second most valuable NFL team behind the Dallas Cowboys. The Redskins “brand management” alone constitutes a $131 million industry. And at Project Cheerleader, prospective beach beauties are instilled with the tremendous significance of making money for the Redskins, if not for themselves. “The Redskins are one of the highest revenue organizations in the NFL,” Lee tells the calendar hopefuls. The team has “more fans come to games, more fans buying paraphernalia, more fans buying calendars,” she says. “Those pictures are important.”

And the team makes sure Redskins cheerleaders look the part. “I remember one time walking off the field and a lady screaming from the stands: ‘My gosh, those cheerleaders make way too much money; look at their earrings!’” cheerleader Jamilla Keene told the Washington Post last year. “We wear a kind of Swarovski-style crystal; it’s costume jewelry, but it looks extremely expensive. So it made me giggle that this lady had this perception that we make a lot of money.”

In lieu of cash, cheerleaders accept consolation prizes. Shiona Baum, who cheered for the team for the better part of the 1980s, represented the Redskins in a televised NFL cheerleading battle, and snagged a red Volkswagen Scirocco that she drove “for years.” Terri Crane Lamb, founder of the Washington Redskins Cheerleaders Alumni Association, was happy to cheer for nothing more than two free season tickets throughout the ‘80s — back then, the seats were worth more.

Other women sign up in the hopes of going on to careers in modeling, acting, or dance. I asked Lamb to list some of the squad’s most successful alums. There’s Debbie Barrigan (’94-’95 and ’99-’01), a dance troupe member in Blast!, a staged take on a football halftime show. Kimberly Vaughn (’98, ’00-‘07) now designs fur and leather handbags, including a pigskin version. Several cheerleaders have moved on to other high-profile positions in the beauty circuit: Michae Holloman (‘02-‘07) was crowned Miss Maryland USA in 2007; Kristianna Nichols became Mrs. America in 1992. Some of the squad’s most prominent alums married success. Janet Patrick is wife to sportscaster Mike. Christy Oglevee (’03-‘07) married Redskins tight end Chris Cooley. Maureen Gardner (’74-‘77) wed future Virginia Governor Bob McDonnell.

Those who don’t get high-profile jobs — or husbands — out of the deal are rewarded with a certain social status. Redskins cheerleaders are members of an elite club, one that Real Housewives star Michaele Salahi infamously attempted to infiltrate. “When I was with the Redskins cheerleaders, I felt like a celebrity,” says Lamb, whose alumni association boasts 900 former cheerleaders dating back to the ‘62 squad, including more than 200 paid members ($15 a year). Even now, Lamb says, “we get asked to golf in tournaments as celebrity golfers.”

Women are prepared from a young age to aspire to the kickline — and to get used to paying for the opportunity. Tylah Lancaster, a 19-year-old from Oxon Hill who attended Project Cheerleader, told me she has wanted to cheer for the Redskins “since I was 3 years old.” At the Redskins team store, girls’ cheerleading jumpers are available for toddlers starting at size 3T ($34). Girls as young as five are recruited to join the Junior Redskins Cheerleaders, who “learn the fundamentals of dance, showmanship and performance” ($325) and perform at halftime shows in a uniform “specially designed to resemble the Washington Redskins Cheerleaders Uniform” ($265). At this year’s final cheerleading auditions, Cheyenne Estep, 6, a “die-hard fan of the cheerleaders,” took mental notes as grown women posed with footballs in bikinis and towering heels to the sounds of Christina Aguilera ($15 to $25 per ticket). During the regular season, Cheyenne and her mother, Kimberly, make the 100-mile commute from Mount Jackson, Va., to FedExField to give Cheyenne the chance to wave her pom-poms on the field.

And no level of front-and-center career success can dampen the cultural cache of a spot on the sidelines. Redskins cheerleaders are engineers, Ph.D. candidates, and Air Force Manpower analysts. At Project Cheerleader, I met a DCPS administrator, a consultant, and a law student all vying for a part-time slot on the squad. “Being a Cheerleader certainly is a great complement to a law career,” cheerleader Marisa says in her squad profile page, on which she poses in a skirt that could moonlight as a belt. In fact, women are required to hold down “a full/part-time job, or attend school full time, or have a family” in order to try out for the team.

And that day job sure comes in handy. Institutional traditions prevent Redskins cheerleaders from really making names for themselves. The gig is stamped with a rough expiration date—though the Redskins don’t enforce an upper age limit, they say their cheerleaders generally range from 18 to 35. The oldest cheerleader in NFL history is 42 years old. In all official capacities, current cheerleaders—including those quoted in this story—are identified only by their first names. “They have fans,” Jojokian says of the surname ban. “Fans who like to look them up.”

At public appearances, cheerleaders are accompanied by bodyguards to ward off inappropriate advances. Pretending that it’s not a big deal is part of the job. “Toward the end of the game, when people are getting belligerent, you just have to keep your head up and smile,” says Donna, 26. “Stay professional,” adds Amanda. “Don’t let the rest of the crowd know it’s affecting you, even if it is.” Sometimes, the crowd commentary requires some internal justification. Cheerleaders should always remember that “it’s about the dancing and performing,” Buffy says. “Not about the outfits we’re wearing.”

The first-name basis may help the cheerleaders evade stalkers, but it also prevents them from building personal brands outside of the boundaries of the team. Agreeing to the terms of the gig “takes a special kind of woman,” says cheerleader Amanda. Says Keene: “You do it for the love of what you do.”

Gregg Easterbrook loves what the cheerleaders do, too. For seasons, the Bethesda-based ESPN Page 2 columnist has used his Tuesday Morning Quarterback platform to plug away at the cheerleader pay problem—when he’s not highlighting scantily clad photographs of the workers in his “Cheerleader of the Week” feature. (Sample commentary: “you might think it would be too cold in Minnesota for bikinis, but you’d think wrong”).

“I don’t think dancing half-naked is exploitation,” says Easterbrook. “But the teams are keeping all the money for themselves. If that’s not exploitation, what is?”

To Easterbrook, the imbalance is clearly sexist. “There’s not a huge mystery as to what’s going on here,” he says. “The NFL is swimming in money. The men involved are paid huge amounts of money. And the women involved are shafted. They’re paid peanuts.”

In order to correct the injustice, Easterbrook says the women will need support outside the world of sports. “The feminist groups could get involved with this, but the number of affected women is very small in the great scheme of things,” Easterbrook says. “And feminist groups are uncomfortable with really good-looking women who want to dance around in bikinis.”

“Like all women, professional cheerleaders are entitled to fair compensation,” counters National Organization for Women action vice president Erin Matson. “This is a job with grueling hours, physical risk, late nights. The NFL rakes in billions each year. Cheerleaders are part of the football culture people pay to see. So why aren’t they being paid fairly? Would we ever have to ask this question about the men on the field?”

One group that isn’t complaining about cheerleader pay: Cheerleaders. “You’re talking to women who have made their deal with the devil because they want to be NFL cheerleaders,” Easterbrook says. “If they argued that they needed better pay for it, they would be dismissed. There’s no job protection, no security, no union, no agent, no nothing. They’re treated as chattel by the teams.”

That arrangement occupies a fuzzy legal space. According to guidelines set down by the Internal Revenue Service, workers like the Redskins cheerleaders fall into a gray area between independent contractor and part-time employee. Several hallmarks of the gig suggest that cheerleaders should be treated as bona fide employees: The team exerts behavioral control over the workers, has significant say over directing how they do the job, and controls many of its business aspects.

Prospective cheerleaders must be 18 or older, have a high school diploma or GED, and hold down an outside career (or “family”). The women are provided exact instructions on which dances to execute and precisely how to learn them; women who miss a practice will be benched for the next game. Unlike contractors, cheerleaders don’t invest in their own gear; they’re provided standard Redskins attire to wear on and off the field, including “uniforms, practice attire, warm-ups, earrings, shoes, boots, and poms.” The control extends down to the follicle. “If we need someone with red hair, and we didn’t get anyone in auditions with red hair, you’re gonna have to dye your hair red,” the team told the women of Project Cheerleader. Once their look is set, cheerleaders are required to maintain the image for the whole season. “Redskins fans are excited about the way cheerleaders look,” former cheerleader ambassador Nicole White says. “They like that consistency.”

The team also controls who cheerleaders date, who they speak to, and what they wear. In 2007, Christy Ogilvee and another cheerleader were kicked off the squad for having a relationship with tight end Chris Cooley in violation of the team’s strict non-fraternization policy. Cooley remains on the Redskins payroll.

In 2009, Marine Lt. Denver Edick contacted local ABC station WJLA to help him surprise his wife Kristin, a Redskins cheerleader, with an on-air homecoming. But when the team punted the story to broadcast partner NBC, the Redskins reportedly informed Edick that if his wife granted an interview to WJLA, she’d be canned. “To threaten to fire his wife—that is objectionable on so many levels that I couldn’t even count them,” WJLA station manager Bill Lord told the Post at the time. The Redskins denied making the threat. (WJLA.com is the sister site of TBD.com.)

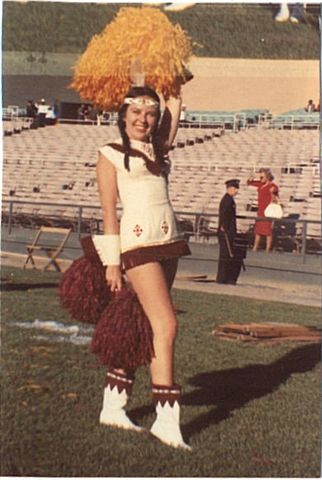

Back in the ‘60s, Redskins cheerleaders took the field each game in white dresses with burgundy fringe, black braided wigs, and feather-adorned headbands—a sexy appropriation of an “Indian maiden” costume. On the final game of the 1967 season, then-squad director Doris Snyder says, the cheerleaders decided to shirk their Indian gear in favor of leotards. “It wasn’t anything flashy,” Snyder says. “It was just a pretty costume. They wanted to do something different.” Redskins brass didn’t like different, and forced the women to change back to their traditional dress before taking the field. The following week, Snyder was fired.

Back in the ‘60s, Redskins cheerleaders took the field each game in white dresses with burgundy fringe, black braided wigs, and feather-adorned headbands—a sexy appropriation of an “Indian maiden” costume. On the final game of the 1967 season, then-squad director Doris Snyder says, the cheerleaders decided to shirk their Indian gear in favor of leotards. “It wasn’t anything flashy,” Snyder says. “It was just a pretty costume. They wanted to do something different.” Redskins brass didn’t like different, and forced the women to change back to their traditional dress before taking the field. The following week, Snyder was fired.

Of course, several aspects of the cheerleading gig diverge from a traditional employee relationship. Cheerleaders are paid a “flat fee for the job,” indicating a contractor relationship. The team does not administer “employee type benefits” to the women. And the business relationship between cheerleader and team is not ongoing—the women are hired season to season, and sitting cheerleaders are forced to compete for their spots each spring. According to the IRS, “there is no ‘magic’ or set number of factors that ‘makes’ the worker an employee or an independent contractor, and no one factor stands alone in making this determination.”

Catherine K. Ruckelshaus, legal co-director of the National Employment Law Project, says that the cheerleaders’ employment situation sounds “horrible,” but not necessarily against the rules. “You could make an argument that all these services that the women are providing forms an employment relationship with the Redskins,” Ruckelshaus says. “But you have to find an employment relationship before any of the protections set in.”

In order to do that, cheerleaders would have to speak up. “The labels the Redskins put on the workers don’t matter if the cheerleaders feel like they are basically part-time employees,” says Ruckelshaus. “Then, they can start to make the argument and build the case.” Once an employment relationship is established, says Ruckelshaus, cheerleaders can demand “minimum wage for the hours they work, overtime if they ever spend more than 40 hours in a week on a photo shoot, and worker’s compensation if they hurt themselves on the job”—like when they perform the kickline’s injury-prone drop splits.

Redskins cheerleaders may not be eager to take up the fair pay banner. But casually, it’s clear that many cheerleaders consider the gig a real job. In one fan video, Dawn lounges in a white bikini and extols the benefits of her employment. “My favorite part of being a Redskins cheerleader is the fact that I get to come to work and I’m in an environment where everyone wants to be there and everyone appreciates their job, and I think that that’s something you shouldn’t take for granted,” she says. “I don’t know that many people that go to work and say that everyone wants to be there.” When Dawn gives interviews on behalf of the team, she identifies closely with the organization, using terms like “we.” Fans, too, closely align the cheerleaders with the brand. “I think some people get the idea that we are cheerleaders all day, every day, just like the football players,” Keene told the Washington Post. Even the team treats the women like major players. “I remember the day that we got our rookie rings at the end of my first season,” Keene told the paper. “I felt like: Oh, wow, I’ve made it.”

The cheerleader pay scale dates back 50 years, to when Doris Snyder organized the first Redskins cheer squad in 1962. Snyder began marching and twirling batons with her twin sister in high school before graduating to pro football majorette with the Baltimore Colts. At no point did she consider monetizing the transaction. “You had to do something after school,” says Snyder, now 84. “It was a social thing more than anything.”

Snyder worked for the Colts in exchange for two season tickets for nearly 15 years. Then, Redskins owner George Marshall poached Snyder, wooing her with $100 a game, two season tickets, and a parking spot in exchange for directing a squad of her own. The women who cheered for her still didn’t get a paycheck. “We always used to say it was our answer to the men’s bowling league,” says Snyder.

And the perception of NFL cheerleading as an extracurricular has persisted for decades. “I saw it as a family,” says Baum, who cheered for the Redskins from ‘79 to ‘88. “I saw it as donating my time to help out with the charities.” Cheering is “like having 39 sisters every year,” Keene told the Post. And “that support system never goes away.” Adds Lamb: “Sure, they put in a lot of time and effort, but they love to do it,” she says. “We built a bond—I call it the ‘Sisterhood of Burgundy and Gold.’” A sisterhood where “we knew what we were getting into before we tried out.”

But the sisterhood comes with its social sacrifices, too. At Project Cheerleader, one woman in the crowd asks the cheerleaders this: “Has it been difficult for you all to adjust your social relationships with people who aren’t cheerleaders?”

“You’re not going to convince all the friends to support you,” cheerleader Dawn says. “It’s a lifestyle. It really is a lifestyle,” Donna adds. “I mean, I love it, I’ve made so many friends. I don’t want to say I’ve switched out friends. But I’ve met a lot of great people here.”

And the Redskins continue to cash in on that lifestyle. In 2009, 150 alumnae performed at a Redskins halftime show. At this year’s cheerleading auditions, former cheerleader Anita Vick volunteered her time autographing and selling calendars. Lamb joined broadcasters and plastic surgeons in helping to judge the competition.

Nowadays, the team is making money off the women before they even make the squad. Back in the ‘80s, the cheerleader auditions were “not open to the public,” Lamb says. “It was just the judges — that was it. Nobody could watch.” Back then, cheerleaders would try out “in tennis shoes and a Danskin, so they could make sure that you were fit,” Lamb says. Now, they audition “in cocktail dresses, in swimsuits. It’s a production now. It’s a business.”

The public auditions for the Redskins Cheerleaders take place on a Sunday afternoon in April at Falls Church’s State Theatre. Attendees pay $15 or $25 for a look at the process, which has already narrowed the field. Of the 400 that tried out, only 58 are left. When it’s all over, the women who invested in the extensions, the makeup, the courses, the personal training sessions, and the glamour shots face less than a 5 percent shot at making the team. Those who fail are encouraged to pitch in another $15 to $25 to support the more successful candidates. “If you don’t make the cut,” Jojokian tells the Project Cheerleader crowd, “come anyway.”

Onstage, the women offer up everything they have. Over a three-hour competition, they execute a slow strip from prom dress to hot pants to bikini. In short choreographed routines to pop songs about sadomasochism (“S&M”) and sexual slavery (“I’m a Slave 4 U”), sideline hopefuls set their faces to fluctuate between babysitter and centerfold. Broad smiles crumble into raunchy winks. Pirouettes land in cheeky butt slaps. Pom-poms linger around explicit areas before reaching into rah-rah poses. Yards of hair is flipped in the exercise. Mid-way through the competition, women auditioning for a spot on the roster are asked to trade their tiny bras and shorts for string bikinis so the judges can finally see just “how beautiful their bodies look.”

Once laced into the swimwear, the women pose with footballs as announcers list off intimate details. Leigh “was adopted.” Sidney hopes to be a “CIA criminal profiler.” Ashley enjoys “performing for our troops and shooting machine guns.” Jessica “loves hot yoga.” Denise “is an engineer.” Michelle loves “anything girlie and talk radio.” Emerald’s “favorite food is old spaghetti.” Tiana likes eating “raw cookie dough with cookie dough flavored ice cream.” Traci was “in Maxim.” Marisa “is learning Portuguese.” Katrina majored in political science at the University of Michigan. Adriana “has seven brothers and six sisters.” Gloria’s favorite quote is “I can do all things in Christ, he strengthens me.”

Forget the biographical fluff — these women can really dance. As they tumble on stage, shimmer lotions and quivering poms hide veins still pumping from the latest high-energy routine. Beyond the steps, the cheerleaders must navigate the contradictions of modern consumerist femininity — glitter and cleavage, six-packs and stilettos, ice creams and doctoral degrees. At first, the juggling act captivates. Then, the 10th set of women retreads the same combination of kicks, flips, and shakes. The opening strains of Christina Aguilera’s “Burlesque” blare out yet again. The 50th near-naked woman plants her legs, drops her hips, and pushes a football toward the crowd.

An hour in, the audience’s beers have drained, but the women still have a good two hours of intense physical activity and constant smiling ahead. I’m reminded of a note from Project Cheerleader: “This is the ‘Academy Award goes to’ moment,” cheerleading ambassadors coordinator Vihky Smith tells the girls. “You’re out there acting like you’re having the time of your life.”

Frank, a Redskins cheerleading enthusiast who declines to give his last name, has shelled out $25 for a VIP view of the proceedings. When I inform him how much these women make per game, he is horrified. “Pro players are making 600,000 times that a game,” he says. “I don’t know what’s right, but I know that’s wrong.”

But upstairs, 27-year-old Kevin hangs silently outside the women’s bathroom. His girlfriend dragged him to the performance. “It was very informative,” Kevin says of the auditions. I ask him how much he thinks these women deserve to make a game. “I don’t know,” he tells me. “Twenty-five bucks?”